GENERAL ELECTRIC Part II -- The U-744

by Ed Sewall

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", November 1998, page 14

In my first article (Crown Jewels -1/98), I described the General Electric

dry process porcelain factory in Schenectady, New York and the earliest pin type

attributable to General Electric, the unmarked U-701. In this article I will

attempt to detail all of the known installations where the unmarked dry process

U-744 have been found and/or documented. I will conclude this series of articles

on General Electric with the history of the unmarked U-935A in the near future.

In addition to the U-701, the unmarked U-744 and U-935A are the only other early

(1895-1897) dry process pin-type porcelain insulators that were thought to have

been manufactured by General Electric. From the dates of various installations

it appears that the U-701 was the earliest of General Electric's dry process

pin types followed by the U-744 and then the U-935A. It appears that General

Electric ceased manufacture of dry process porcelain pin types in Schenectady in

late 1896-early 1897.

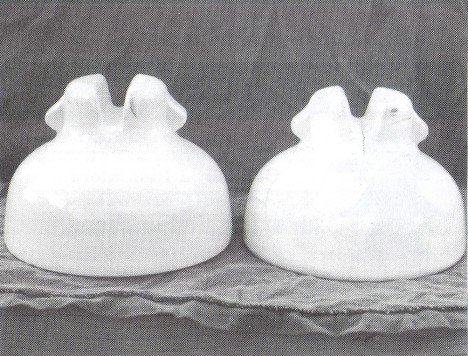

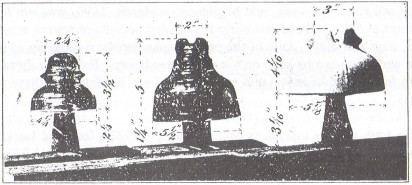

Front view of two U-744's.

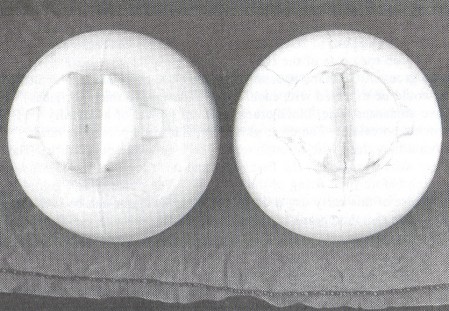

Top view of two U-744 's. Note obvious mold line on left

specimen and obvious

dry process bracing on right specimen.

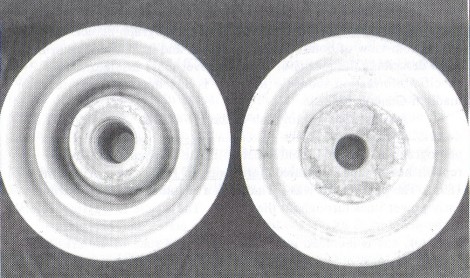

Bottom view of two U-744's. Note porous, granular

dry process porcelain on

broken inner skirt on

the insulator to the right.

The U-744 has only been found unmarked, and consists of a white dry process

body with triple petticoats. Usually a highly visible mold line over the crown

is present as well as one along the outer edge of the skirt as a result of

forming in a 3 piece mold. A single ear is located on each side of the crown to

secure the tie-wire instead of a wire groove. On many specimens the ears are

often chipped or broken as would be expected with such a fragile design. Some

specimens have numerous, fine, black cracks that are typical of an old dry

process porcelain. The clear glaze over the white porcelain varies from a thin

glaze with a rough texture to a glassy smooth finish. The inner skirt was used

as the firing rest and the glaze was wiped off with a cloth before final firing

of the insulator. The porosity and granular structure of this early dry process

porcelain insulator can be seen quite clearly in the photograph of the bottom of

a U-744 with the inner petticoat broken out.

Although this insulator is the most

common of the three classic dry process General Electric's, it is the most

difficult to find documentation of its use. Rumors often heard regarding

supposed sources of the U-744 including trolley lines in Connecticut, the Pomona

line, as well as various lines in Colorado and California. Based upon the

evidence I can find, most of these sources appear to be only partially based

upon fact and many may be just pure speculation.

The information that is

available on the U-744 includes several early photographs. A photo of the U-744

alongside a U-935B (Imperial) is included in a book by Maurice Oudin entitled Polyphase Apparatus and

Systems, dated 1900. This photograph depicts the front

and bottom view of both of these insulators and is in a section of the book

describing the merits of porcelain over glass insulators. No specific

information about the insulator is included nor is any mention made of General

Electric.

Another nice photograph of the U-744 was in an 1895 article

describing the Niagara power system in Cassiers Magazine. This photograph as well

as the information in the original article was republished in a book entitled

Harnessing of Niagara also printed in 1895. The photograph was included in a

chapter describing various early power lines throughout the world. The article

in Cassiers refers to the photograph of the U-744 as a double petticoated

porcelain insulator, and is included in a discussion of the state-of-the-art of

power line construction in 1895. Further description states that bare conductors

should be supported on "heavy double petticoated porcelain insulators as

shown on this page (the U-744 photo) mounted on wooden crossarms". The

article continues stating that these insulators have withstood a pressure of

90kv without puncture and that "these insulators are sometimes made in two parts, separated by oil" as well as

"It is very difficult to keep the oil perfectly clean and the best practice

today is to use air separation, which under conditions of service is probably

more reliable than separation of oil". This description of the use of oil

with the U-744 is very interesting as oil-type insulators were also described

for the earlier Taftsville Connecticut power line where the U-701 was found (see

CJ Jan. 1998). It is probable that by 1895 the use of oil was found only to be

good in theory and impractical in the field. Nothing resembling the second oil

holding section of these insulators that is described in Cassiers has ever been

found.

The best available information on the use of the U-744 comes from the

article High-Voltage Power Transmission, by Chas. F. Scott that was run in the

June 30, 1898, journal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. This

article describes the testing of various pieces of equipment including

insulators on an experimental alternating current line at Telluride, Colorado in

the period from 1895-1896. This information was first reported in Crown Jewels

in Jack Tod's column by Matt Grayson in September 1978. The Telluride test

facility included a 2.25 mile line that ran from Ames, Colorado to the Gold King

stamp mill. This article includes clear photographs of the test line where three

insulator styles were tested. The three styles included the CD244, CD287 and

the U-744. The photograph, including measured dimensions of the U-744 is so

clear you can see the mold line over the crown. The U-744 is described as a

double petticoat insulator that was initially strung with No.6 Band S gauge

galvanized iron wire and was later re-strung with No.6 B & S copper wire

with a diameter of 0.162". Tests on this line started in December 1895 and

initially the line was run between 25kv -33kv for a period of several days. In

January, 1896, the line was energized at 45kv and run for a week, and beginning

in March, 1896, was run for 37 days at 50kv. These test periods included periods

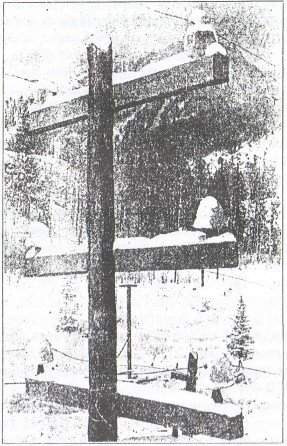

of severe wind, rain, dust and snow. One of the photographs depicts a close up

of the pole and snow can be seen on top of the insulators. Evidently there were

few problems associated with any of these insulators in these tests.

At the time

of this test (1895-1896) the only companies manufacturing high voltage

insulators were Thomas (U-923C for Fred Locke up until October 1895), Imperial

(producing the wet-process U-923A for Fred Locke in late 1895) and General

Electric for their own transmission projects. Pass & Seymour had produced

small (telegraph size), cast, wet process insulators up until the 1895-1896

period before they are thought to have ceased manufacture of pin types as a

result of the high cost of their product. The U - 7 44 does not have any

characteristics that indicate anyone but General Electric produced them.

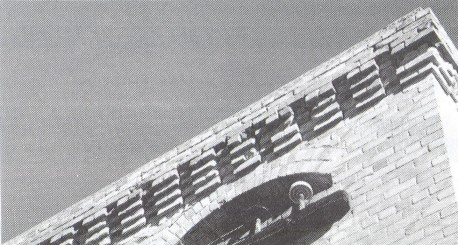

50,000 Volts on Large Glass Insulators (Upper Cross-arm) and

on Porcelain

Insulators (Lower Cross-arm.)

(Photo from AlEE, June 30, 1898.)

U-744 insulators

on bottom two cross-arms in the photo.

Insulators used on High-Tension Tests at Telluride.

(Photo from AlEE. June

30, 1898.)

U-744 is insulator on far right.

At no

point in the June 30, 1898, AlEE article on the Telluride test line is General

Electric mentioned or the manufacturers of any of the insulators described.

However, close inspection of this insulator reveals very similar design and

manufacturing characteristics to the no name U-701 as well as the U-935A,

insulators that have been attributed to GE with near certainty. It also appears

that the experimenters in this test took insulators that were in use on various

existing transmission lines at that time to conduct an objective comparison of

the best available power insulators. It is probable that the Fred Locke U-923

series manufactured by Thomas and Imperial were in such short supply and/or so

new to the industry that they were not available for testing and did not have a

track record like the U-744.

A second installation where the U-744 was used

was on the Big Cottonwood line near Salt Lake City, Utah. Barrie Rufi has spent

a lot of time searching the Big Cottonwood Canyon area as well as the power

plant itself. Last year Barrie removed a U-744 still mounted on a pin from the

Big Cottonwood Canyon power house. It is possible that the U-744 Barrie removed

was the last one in service, a full 101 years after it was installed! Barrie

informed me that he also found numerous broken U-744's around the station and

along the line. As you can see from the photograph Barrie took of the U-744

before he removed it, a broken brown unipart, probably an Imperial U-746 was

mounted next to it. The only other pin types Barrie recalled seeing on this line

were a small, brown, two piece multipart.

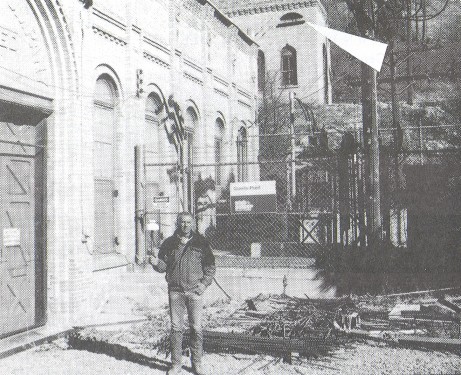

Photograph depicting U-744 mounted on the

Big Cottonwood Power Plant that

Barrie Rufi Removed in 1997.

(Photo courtesy of Barrie Rufi.)

Barrie Rufi holding U-744 on original wood pin.

Insulator came from small crossarm under window

in top right corner of photo.

(Photo

courtesy of Barrie Rufi.)

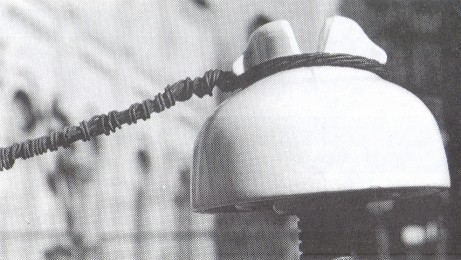

Closeup of the U-744 Barrie Rufi removed from Big Cottonwood Plant.

(Photo

courtesy of Barrie Rufi.)

The Big Cottonwood power plant is described in an article in Electrical World

& Engineer dated March 30, 1901. This article describes three (3) power

transmission plants and distribution systems in the Salt Lake City and Ogden,

Utah area that in 1901, were under ownership of Utah Light & Power Company.

One of these was the Big Cottonwood hydroelectric plant located 14 miles

southeast of Salt Lake City in Big Cottonwood Canyon. The Big Cottonwood plant

and transmission line are described as a General Electric installation completed

in 1896. According to Fred M. Locke, A Biography (Gish 1994), this line was

installed in June of 1896. The plant contained 4 Pelton waterwheels driving

three-phase, 500 volt General Electric generators. The 500 volt generators were

stepped up by six, 250kw transformers to 10kv before leaving the power house.

The transmission line to Salt Lake City consisted of two, three-phase circuits

of No.2 wire on porcelain insulators. The insulators on this line were described

as "among the first high-tension insulators turned out and were made by the

dry process". Evidently the dry process U-744 units on the Big Cottonwood

line were prone to puncture, resulting in burning off the pins. In addition,

boys routinely shot at the insulators and this was considered the most serious

problem on the line. Further description of these insulators states that "Fully one-third of them have had to be replaced" (as of 1901).

It was

previously thought that the Electrical World description referred to the no name

U-935A being replaced with Imperial U-935A and U-935B insulators. This appears

to be true for the Ogden-Salt Lake City line where no name U-935A insulators

were used (see CJ Sept. 1994, pg 11-13). Based upon Barrie's observations, it

does not appear that any of the U-935A's were found or used on the Big

Cottonwood line. Assuming this is true, the article must be describing the U-744 as the dry process insulators that needed to be replaced.

Barrie also

provided me with some historical pamphlets and a book that Utah Power &

Light Company produced. The pamphlets contain early photographs of the

transmission line leaving this plant and the white U-744's are visible on the

lines. Barrie also photographed a pole on the line still in service near the

plant and it contains three brown "Redlands" style uniparts, appearing

to be Imperial U-746's. These must have been some of the replacements for the

U-744 dry process units.

It is quite possible that the March 30, 1901 Electrical

World & Engineer article was incorrect and should have referred to the Ogden

line where unmarked dry process U-935A's were definitely replaced with Imperial

U-935A and U-935B insulators. As I have discovered researching these old journal articles, they were not always 100% accurate.

Elton also describes in his Fred Locke book that Fred Locke had been asked to

fill an order for 4,100 porcelain insulators (U-923A) for Mountain Electric

Company of Denver in August of 1896. Interestingly, these insulators were

ordered for the Big Cottonwood Canyon transmission line. However, none of these

have been found on this line that I am aware. of. I suppose it is possible that

these insulators were to be used on another power plant and line known as the

"Utah plant", which was located at the tailrace of the Big Cottonwood

plant. This line, started up in 1897, is known to have used Imperial insulators

and this may be what the Fred Locke order was for.

The third installation of the

U-744 that can be verified was in the Fresno, California area. Bill Heitkotter,

a former lineman and pioneer insulator collector provided some interesting

information to me on his discovery of U-744s in this area. According to Bill,

U-744s were used on an old San Joaquin Light and Power Company line that ran

between Wishon and Fresno, California. He said they were also used on scattered

12kv lines throughout Fresno and Selma. Bill found an old Pacific Gas and

Electric (formerly San Joaquin Light and Power Company) dump in Selma that

contained numerous broken U-744's as well as several whole insulators. I have

not found any journal articles on this area, but I would bet that these lines

are directly connected to local General Electric power plants.

As described in

my last article on the General Electric porcelain factory, it is evident that

General Electric manufactured dry process porcelain pin-type insulators for

their early power plants and transmission lines. Other than the test conducted

at Telluride (an objective test of transmission line equipment run as part of a

Westinghouse project), all of the power plants and transmission lines associated

with the U-744 were totally equipped by General Electric. The other companies

(Thomas, Imperial) manufacturing porcelain power insulators at this time do not

appear to have been possible manufacturers of these insulators. Although we

still cannot say with 100% accuracy that General Electric manufactured the

U-744, all evidence points to them as the source of this classic piece.

The

U-744 as an insulator that is fairly regularly seen on trade lists as well as

at shows. Approximately 25-35 of these insulators are thought to be in the

hobby, although there may be more. The book value on these is $30-$50, with most

selling in the $30 range. Considering the number of specimens available to

collectors and the fact that the U-744 was one of the very first porcelain

power pieces in use in this country, this seems to be a real bargain.

References:

Cassiers Magazine, 1895.

Crown Jewels of the Wire, Nov 1978, Sept. 1994 &

Jan. 1995

Value guide for unipart and multipart porcelain insulators. E. Gish,

1995.

Harnessing of Niagara. 1895.

Polyphase Apparatus and Systems, Maurice Oudin,

1900.

Journal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, "High

voltage power transmission", C.F. Scott, June 30, 1898.

The Electrical

World and Engineer, March 30, 1901.

Fred M. Locke. A Biography, E. Gish 1994.

The Power To Make Good Things Happen, J.S. McCormick, 1990. Utah Power &

Light Co.

Insulator Research Service

Bill Heitkotter - Personal

communication.

Barrie Rufi - Personal communication.

|